Semi-differentiability

In calculus, a branch of mathematics, the notions of one-sided differentiability and semi-differentiability of a real-valued function f of a real variable are weaker than differentiability.

Contents |

One-dimensional case

Definitions

Let f denote a real-valued function defined on a subset I of the real numbers.

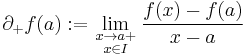

If a ∈ I is a limit point of I ∩ [a,∞) and the one-sided limit

exists as a real number, then f is called right differentiable at a and the limit ∂+f(a) is called the right derivative of f at a.

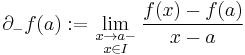

If a ∈ I is a limit point of I ∩ (–∞,a] and the one-sided limit

exists as a real number, then f is called left differentiable at a and the limit ∂–f(a) is called the left derivative of f at a.

If a ∈ I is a limit point of I ∩ [a,∞) and I ∩ (–∞,a] and if f is left and right differentiable at a, then f is called semi-differentiable at a.

Remarks and examples

- A function is differentiable at an interior point a of its domain if and only if it is semi-differentiable at a and the left derivative is equal to the right derivative.

- An example of a semi-differentiable function, which is not differentiable, is the absolute value at a = 0.

- A function, which is semi-differentiable at a point a, is also continuous at a.

- The indicator function 1[0,∞) is right differentiable at every real a, but discontinuous at zero (note that this indicator function is not left differentiable at zero).

Application

If a real-valued, differentiable function f, defined on an interval I of the real line, has zero derivative everywhere, then it is constant, as an application of the mean value theorem shows. The assumption of differentiability can be weakened to continuity and one-sided differentiability of f. The version for right differentiable functions is given below, the version for left differentiable functions is analogous.

Theorem: Let f be a real-valued, continuous function, defined on an arbitrary interval I of the real line. If f is right differentiable at every point a ∈ I, which is not the supremum of the interval, and if this right derivative is always zero, then f is constant.

Proof: For a proof by contradiction, assume there exist a < b in I such that f(a) ≠ f(b). Then

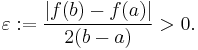

Define c as the infimum of all those x in the interval (a,b] for which the difference quotient of f exceeds ε in absolute value, i.e.

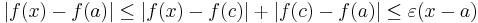

Due to the continuity of f, it follows that c < b and |f(c) – f(a)| = ε(c – a). At c the right derivative of f is zero by assumption, hence there exists d in the interval (c,b] with |f(x) – f(c)| ≤ ε(x – c) for all x in (c,d]. Hence, by the triangle inequality,

for all x in [c,d], which contradicts the definition of c.

Higher-dimensional case

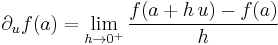

This above definition can be generalized to real-valued functions f defined on subsets of Rn. Let a be an interior point of the domain of f. Then f is called semi-differentiable at the point a if for every direction u ∈ Rn the limit

exists as a real number.

Semi-differentiability is thus weaker than Gâteaux differentiability, for which one takes in the limit above h → 0 without restricting h to only positive values.

(Note that this generalization is not equivalent to the original definition for n = 1 since the concept of one-sided limit points is replaced with the stronger concept of interior points.)

Properties

- Any convex function on a convex open subset of Rn is semi-differentiable.

- While every semi-differentiable function of one variable is continuous; this is no longer true for several variables.

Generalization

Instead of real-valued functions, one can consider functions taking values in Rn or in a Banach space.

See also

- Derivative

- Directional derivative

- Partial derivative

- Gradient

- Gâteaux derivative

- Fréchet derivative

- Derivative (generalizations)

References

- Preda, V. and Chiţescu, I. On constraint qualification in multiobjective optimization problems: semidifferentiable case. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 100 (1999), no. 2, 417--433.

![c=\inf\{\,x\in(a,b]\mid |f(x)-f(a)|>\varepsilon(x-a)\,\}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/dc682b276e01520b0926686531a6457c.png)